Some can view sport as a question of make-it or break-it. But questionable training cultures and concerns around toxic training environments have been under the spotlight in recent times. The Nike Oregon project and British Cycling, to name two of the more high-profile cases, have been rocked by accusations of a culture of bullying, shady practices and medical mismanagement (https://www.bbc.com/sport/athletics/51599747). These accusations often centre around dominant, didactic coaches. Some athletes have now broken their silence and given their perspectives on the culture inside these highly successful teams. Are these isolated cases? Doubtful. But what is it about the culture of professional sport in particular that enables such environments to be created?

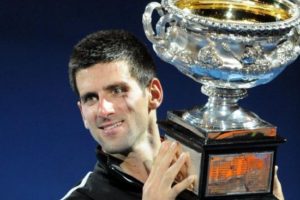

Such sporting environments are entirely orientated around one aim- maximising human performance with the aim of winning sporting events. They are often organised around a coach, or team of coaches, that operate in a dominant, hierarchical fashion. The lead coach can be loosely accountable to an owner or funder who may only have eyes for results. This lead coach then exerts control and considerable influence over all other members of staff and athletes involved in a given team. A lead coach can adopt a variety of styles, but one possible perspective they can take is that they consider the athletes as subjects under their command. The coach can also adopt the perspective that only select few of the athletes under their charge will reach the desired level. But for the elite coach a select few may be all it takes to reach their goal; the rest of the athletes can be considered disposable, or even as experimental subjects. As a result, athletes can be subjected to a culture of make-it or break-it. If an athlete doesn’t make-it the coach can insist on trying alternative, experimental methods. If these experimental methods don’t work then the coach may have only lost an already struggling athlete but learned something along the way. To illustrate this example, consider a group of say 5 elite athletes. It may not be clear early in these 5 athletes’ careers which of them will have the capability of winning an Olympic Gold. A coach who has a make-it or break-it attitude can drive all 5 of the athletes to the brink, with the aim of squeezing out every last 0.1% of improvement possible. If a make-it or break-it attitude is coupled to a belief that the athletes may back off when things get really tough, the coach may justify an approach of maintaining intensive pressure in an attempt to force the athletes to improve. 4 might break, but 1 might make it. This may sound perfectly reasonable and this logic is evident in many coaches, across many sports and performance levels. However, there are a number of issues with this standpoint. One problem is that the coach effectively adopts a position where they can disregard an athlete’s wellbeing and disregard feedback from the athlete themselves. What one person considers toughness can easily cross another’s line for bullying or even abuse. If the coach holds a dominant position and always calls the shots then an athlete under them is left with little power. This appeared evident at the Nike Oregon project where athletes were apparently coerced into taking certain medications without medical need in order to attempt to boost performance. There was evidence of struggling athletes being particularly targeted for such interventions. Such powerlessness on the part of the athlete leads on to another issue, the issue of athlete responsibility and learning. If we consider an individual sport, tennis for example, then any athlete involved at the elite level will be looking to optimise their performance. In other words, become the best that they can possibly be. In order to do this, they will need to avoid major injuries, learn tactics, learn their own strengths and weaknesses, learn how their body responds to training loads and how well they recover, learn to control their emotions, one could go on. If a dominant coach has already decided that only their vision is valid, then only their pathway becomes acceptable. It you don’t make it you can try harder, take experimental ‘help’ or quit. Such coaches are therefore imposing control and choice on an athlete and hampering potential learning. An increasing body of evidence shows that factors such as mental load, satisfaction with life-situation and mood all influence not only short-term performance but the risk of injury and the potential for recuperation from training and injury. An athlete that learns about themselves and has the flexibility to adjust has a greater chance of optimising their performance. The athlete should also be afforded the basic rights over their own body to do so. A coach may achieve better results through facilitation than through despotism, but they will also stay on the right side of ethical lines.